Training hard comes with a price. That price is usually some sort of nagging pain or injury that we typically just assume will be with us for the rest of our lives.

“Oh yeah, it is just my bad shoulder. It always aches after I bench.”

“You know how that knee is. There is usually a dull pain in there all the time.”

Often times, these injuries can be alleviated by some soft tissue work and stretching. There are a variety of different types of soft tissue work:

Active Release Techniques (ART)

Myofascial Release (MFR)

Neuromuscular Therapy (NMT)

And the list goes on and on. I believe that all types of soft tissue work have their place and what may be more important than seeking out a specific type of soft tissue work is just getting SOMETHING done by a skilled therapist

A term that gets thrown around by massage therapists, physical therapists and chiropractors which has recently been making its way into the strength and conditioning world, is the term “trigger point.” Since people seem to be talking about trigger points more and more, I decided to give you are run down of exactly what a trigger point is, why we should care about them, and what we can do about them.

What is a trigger point?

While some may tell you that trigger points are tender areas in the muscle, this is actually not entirely true! One key characteristic of trigger points is that they are tender to touch. However, not every tender area is a trigger point.

If an area of a muscle is simply tender but does not have the other characteristics of trigger points, then the area is just a “tender point”. These tender points are areas of congestion, where tissue may be ischemic (lacking blood flow), fibrotic, or there may be a lot of scar tissue matted down in the particular area of stress.

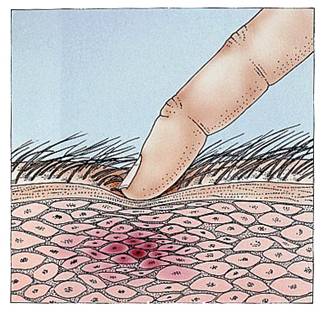

Trigger points are areas of taut, hyper-contracted bands/nodules within a muscle. They are tender to touch and have a predicted pain referral pattern. These hyper-contracted nodules within the muscle are palpable and will often feel like little peas or semi-cooked spaghetti. A visual example, would be this picture of some trigger points inside the Sterocleidomastoid:

As you can see, there are a few small contracted nodules, within the fibers that are at normal resting length.

Trigger points can be either active or latent.

A latent trigger point means that it only sends its pain referral pattern when you touch it. For example, if you take a tennis ball and place it between your scapula and your spine, you may push into a trigger point in the rhomboids, which will give you this radiating or dull ache all over the upper back area. If you didn’t push into that area with the trigger point, you would not know it was there. This is a latent trigger point. It only refers when you press into it.

An active trigger point is one, which is currently referring its myofascial pain response. A good example of this, is if you ever had a headache, and you pinched your upper traps, and in doing so were able to produce your symptoms (i.e., the headache or that ache through the top of your head and behind your eyes), congratulations, you found an active trigger point!

Trigger points usually can be found in clusters. So, if you de-activate one (I’ll tell you how in a second), then you have to search out and try and de-activate the others within that muscle. This could take some time and may be very intense, so you might want to do it over several sessions.

Another thing to consider is that trigger points are not just located within the belly of the muscle. They can also be located in tendonus attachment of the muscle and, even some trigger point referral patterns have been documented ligaments – good examples of this would be the pain referral pattern for the sacrotuberous ligament, which refers a pain pattern down the back of the leg and into the calf (similar to what people may diagnose as or call sciatica) and the pain referral pattern for the iliolumbar ligament which is can be felt in the groin or pain on the outside of the hip (what some may diagnose as or refer to as trochanteric bursitis).

What Muscles Can Develop Trigger Points?

No man is safe!

Any muscle can develop a trigger point and there are several books documenting where these trigger point referral patterns are. (Travell and Simons opus Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction: The Trigger Point Manual; Vol 1 [the upper extremity] and Vol. 2 [the lower extremity] are the most comprehensive and widely accepted books on the topic of trigger points).

A lot of times, trigger points can be found in muscles, which are antagonistic to muscles that are constantly contracted. An example of this would be the infraspinatus, always trying to exert an eccentric force on someone’s shoulder who sits at a desk all day, typing away in a chronically internally rotated position. After a while, the infraspinatus gets tired and lengthens. However, there are bands of that muscle, which stay contracted (trigger points!) to try and counteract the internal rotation force.

Over time, these bands can present their pain referral pattern. One of the pain referral patterns for the infraspinatus is to the front of the shoulder, where people will often say that they got a diagnosis of bicipital tendonitis or impingement. It is not uncommon for someone to come to see me with pain in the front of his or her shoulder (near or around the biciptal groove) and say that they think they have impingement.

Upon inspecting their infraspinatus, I can find the trigger points and when I push into them, and ask how it feels and if they feel pain or sensation anywhere else, they comment that they feel the pain in the front of their shoulders and it is the same pain that they feel through out the day. On more than one occasion, I have de-activated trigger points in someone’s infraspinatus and they left totally pain free.

Trigger points can also be found in muscles that are under chronic contraction. A good example of this may be the upper traps or the sub occipital muscles (or even the pectoralis major from the above example! Another common example would be trigger points in the psoas with people who are always in an anterior pelvic tilt).

The upper traps or sub occipitals may develop trigger points from being over contracted all day as individuals sit at their desk with poor posture. Both of these muscles have pain referral patterns that go up into the head and behind or just above the eyes. It is no wonder that people who work desk jobs get such frequent headaches!!

So basically, any muscle can develop a trigger point for any number of reasons:

From Clinical Applications of Neuromuscular Techniques by Leon Chaitow and Judith Walker-Delaney (Vol 2, pg. 20):

Primary activating factors:

Persistent muscular contraction, strain or overuse (emotional or physical cause)

Trauma (local inflammatory reaction)

Adverse environmental conditions (cold, heat, damp, drafts, etc.)

Prolonged immobility

Febrile illness

Systemic biochemical imbalance (e.g. hormonal, nutritional)

Secondary activating factors:

Compensating synergist and antagonist muscles to those housing triggers may also develop triggers

Satellite triggers evolve in referral zone (from key triggers or visceral disease referral, e.g., myocardial infarct)

Infections Allergies (food and other)

Nutritional deficiency (especially C, B-complex and iron)

Hormonal imbalance (thyroid, in particular)

Low oxygenation of tissues

The key is knowing where to look and what to do when you find one!

Why Should We Care About Trigger Points?

The first and obvious reason to care about trigger points is BECAUSE THEY HURT! Basically, anything that hurts is going to alter the way that we move. This in turn leads to other dysfunctions and problems and potentially more trigger point development.

Aside from altering the way that we move, when we are in pain we (psychologically) don’t feel good! No one likes to be in pain or miss time playing their sport or training because they hurt.

Common clinical characteristics of trigger points are:

There may be pain upon contraction – Again, no one likes to hurt. If it hurts to contract, we don’t want to contract.

Pain during stretching of the muscle at certain ranges of motion – If it hurts to take a muscle through a certain range of motion, then we stop doing it or we limit that range of motion, leading to more problems.

Muscle weakness – This is a big one!! If muscles are weak, then they can’t optimally do their job. An example of this is trigger points in the psoas or the gluteus medius, making those muscles test weak, and causing other problems down the chain. This is also an important aspect, as we often times think of muscles that test weak as muscles that need to be strengthened. However, what happens when you try and strengthen a muscle (causing it to contract more) that has taught bands, which are already hyper-contracted? Not a whole lot, that’s what! You may end up just chasing your tail trying to help that person

In short, we should care about trigger points because they can negatively affect our performance.

What Can We Do About Trigger Points?

So now that we know what trigger points are, how they develop and why we should care about them, most people are probably wondering, “How do I get rid of them?”

The method of getting rid of trigger points isn’t that hard. You just have to know what muscles to check, how to access the muscle (not just how to find it, but knowing which direction the fibers run can be very helpful), and how to release the trigger point.

If you are rolling on a foam roller or tennis ball or if you are performing trigger point therapy on someone else, you are going to want to look for trigger points that refer to the area of the body that the person is complaining of pain in. A great book that I recommend often is The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook: Your Self-treatment Guide for Pain Relief by Clair Davies.

It’s basically a “how to” book for finding trigger points and where there pain referral patterns are. Each chapter deals with a region of the body and the first page of each chapter has various places that people may feel pain (i.e., anterior shoulder pain) and then the muscles and page numbers those muscles can be found on which refer pain to this area (i.e., the muscles which can refer to the anterior shoulder are infraspinatus, anterior deltoid, scalenes, supraspinatus, pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, biceps, latissimus doris, coracobrachialis). It then tells you exactly how to work those muscles. It may be the best $20 you ever spend (assuming that you’ve already purchased a foam roller).

Once you have found and confirmed your trigger point, you need to set up a barrier, which breaks apart the actin and myosin (the contractile proteins within the sarcomere) which are bound together due to the chronic contraction in the specific band of the muscle.

This barrier can be created with your fingers (as in the picture) or with any one of the self- care tools available today (e.g. foam roller, the Stick, Thera-cane, trigger point ball, tennis ball, etc). A lot of people like to take the foam roller and roll back and forth on it. This is okay, as it helps to address the fascia, improves circulation to the tissue and can help to break up adhesions. But if you want to deactivate the trigger point, you need to stop on the tender area that is referring pain and hold your pressure until it begins to release and the pain starts to dissipate.

The amount of time that you hold the trigger point has been debated over the years, but it appears that approximately 8-12 seconds is the accepted amount of time. It is important to note that if you are pushing and it isn’t releasing, you may be giving it to much pressure and just blasting through superficial tissue and/or more superficial trigger points.

Also, if the trigger point doesn’t release after a short period of time, you may want to mark the area (with a pen or something that will wash off) and work other areas of the muscle and come back to it, as trigger point therapy can get very intense and this intensity may not allow the trigger point to release right away. The real key is to give the trigger point just enough pressure to start to feel it release (and confirm that with a slight dissipation of the referral symptoms) and then start to go deeper and work through the next barrier.

How much pressure is enough?

A little bit goes a long way with this. In the past, it was suggested that you hold pressure the trigger point at the individuals’ pain tolerance of a 7-8/10 (10 being excruciating pain). It is now accepted that even a 7-8/10 may be to high to get a proper release, so authors and researchers suggest holding the trigger point at a level of a 5/10 until the individual experiences a decrease in symptoms, at which point you can either go deeper into the tissue (look for trigger points that are in deeper muscles) or move to another location and search for trigger points (the trigger point clusters that I referred to above).

It is important to know that this sustained compression is what will help to alleviate the trigger point. If you only hold for a short period of time, and don’t continue with the treatment, the shortened nodule within the muscle will return to its previous state and very little therapeutic benefit will be gained.

So, to review:

Find the trigger point

Hold pressure at a 5/10

Wait for the tissue to release (you can feel it soften under your skin or, the person will begin to feel a decrease in the pain referral pattern)

Once the tissue releases and the referral starts to dissipate, either go deeper into the tissue or move on and look for other trigger points in the cluster.

Once the trigger points have been de-activated and “order has been restored to the muscle,” you can go ahead and roll the muscle out to promote some blood flow to the area, stretch the tissue (if it is a muscle which needs stretching) and strengthen the tissue.

Things To Consider:

Remember, not all tender areas are trigger points. They may be tender points where tissue is ischemic, scarred up, or fibrotic. This may require other forms of soft tissue therapy.

Trigger points are usually not the only problem. They are usually part of a bigger problem that has to do with other soft tissue dysfunctions. Seek out a therapist who can work with you to determine what underlying problems you may have.

Self Care is important! Make sure you are foam rolling and working on your soft tissue. Make sure your training program is developed properly to limit tissue stress and overuse.

Soft tissue work, foam rolling and proper strength exercises are essential in making sure that your tissue stays healthy and you stay pain free.

Be aware of your activities of daily living and your posture, so that you are not putting unnecessary stress on structures that don’t need it. So much of our pain and dysfunction comes back to how we operate on a daily basis. Altering activities of daily living, while difficult, is crucial in making lasting changes in your soft tissue.

Just because you de-activate a trigger point doesn’t mean that it can’t return.

Always seek medical attention if you feel there is something more serious going on

References:

Simons D. Understanding Effective Treatments Of Myofascial Trigger Points. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2002. 6(2) 81-88.

Chaitow L, Walker-DeLany J. Clinical Application of Neuromuscular Techniques, Vol. 1: The Upper Body. Elsevier Limited. 2000.

Chaitow L, Walker-DeLany J. Clinical Application of Neuromuscular Techniques, Vol. 2: The Lower Body. Elsevier Limited. 2002.

Davies C. The Trigger Point Therapy Workbook: Your Self-Treatment Guide For Pain Relief. 2nd ed. New Harbinger Publications, Inc. 2004.

Archer P. Therapeutic Massage in Athletics. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. 2007.

Lecture notes from: Neuromuscular Therapy – American Version: Care of Soft Tissue Pain and Dysfunction. Judith Delany. International Academy of Neuromuscular Therapies: NMT Training Center.

Great article Patrick-very easy to follow and understand!

Patrick,

What do you think of Claire Davies’ preferal of a rolling stroke over a static compression for trigger points?

Also, what do you think of Cross-Fiber Friction for trigger points?

I’m a Massage Therapy student, and I’m still experimenting with the most effective methods for deep tissue-type work. So far, static compressions don’t seem too effective, unless followed by or combined with something that draws blood to the area. I’ve found that XFF, gliding or rolling compressions, and pumping compressions are the most effective thus far.

I’m mostly working on palpating and locating the muscles, moreso than trying addressing actual problem areas, so you can take my limited experience with a grain of salt.

delee1000,

Thank you for taking the time to check out 8weeksout.com, read the article, and comment.

To address your first question, I think Claire’s book is a good “cliff notes” version of what to look for. It is obviously not as comprehensive as Travell and Simons text, Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction Vol. 1 and 2, which are considered the “bible” when it comes to this topic.

If this is a topic you are interested in I’d encourage you to check out the Travell and Simons books. Chaitow and DeLany’s text, Clinical Application of Neuromuscular Techniques Vol. 1 and 2 are also two excellent must reads for any manual therapist and they go very in depth into trigger point therapy (amongst many other things).

RE: Static compression vs. Friction

Claire Davies prefers friction and Travell and Simons will tell you static compression (or some other technique like dry needling or spray and stretch, which Dr. Travell was very fond of).

There isn’t really a “right” or “wrong” and I’ll address that in a second. With regard to your comment, “So far, static compressions don’t seem too effective…”, I’d encourage you to hang in there and really hone your palpation skills. Being new to doing this stuff means that there is a long road to walk in terms of learning what to feel, how to feel, and then what to do with the information your hands are gathering. If static compression is “not effective” you may not be in the right spot. Or, you may be working the wrong structure? Or, perhaps what you have is not really a trigger point and the tool you are trying to use (ischemic compression) is the wrong tool for the job.

Experimenting as you are doing is a good thing and like I stated, there is no right or wrong. Friction can get a good result in certain situations and it is knowing when and what situations to use it in that is the key. Sometimes friction can be to much of a stimulus to the nervous system and you may get a negative result from the treatment. Additionally, sometimes too hard/deep compression can give you a negative result and cause the skin to tighten up (a sympathetic response). So you will need to play with it to see what gives you the best result.

There is a difference between working “deep” and working “specific”. The more specific I am, the less “deep” I have to work, as I am were I need to be (the right muscle, the right layer of tissue, the right fiber direction, etc). Sometimes I don’t need to do anything more than just being very superficial and stretching the skin. Other times I may have to go with harder friction or compression and in other situations, having the client perform gentle active movements as I take the tissue in a specific direction may yield the result I seek.

At the end of the day, the goal is two-fold:

1) Modulate the tone of the tissue where necessary

and

2) Figure out the best way to influence the clients nervous system to get the result that you want. Different people respond to different things and clients are not a homogenous group. Everyone is an individual and the better you can get at gathering information (both subjective and objective) the better you can get at influencing their body to achieve what you want.

Hope that helps answer your question.

Patrick

I love your writing, Patrick. So simple and easy to comprehend. I’d be interested in follow ups to your common methods of soft-tissue treatment. I have been doing some reading on NMT, but don’t have any visual or first-hand experience of it.

Lance,

Thanks for the kind words.

Methods of treatment is a tough one. When it comes down to it, there only a few techniques/methods:

– Compression

– Gliding

– Kneading

– Friction

Everything else is pretty much a derivative of those four. The real key is knowing where to work and why you are working there, and this comes down to your ability to make distinctions in how things feel.

What have you been reading about NMT? Neuromusclar therapy is not so much a technique, but more a way of developing a thought process. A way to look at things and trying to make sense of the picture.

If you’d like to talk specifics, please feel free to call me.

Patrick

Do you think that different areas respond differently to different techniques?

For instance I’ve found static compression followed by rolling back and forth to be awesome for my IT band and quads particularly close to my knee, but for my upper traps the pain can be so spread out, broader strokes seem to work better.

Maybe it’s because there not really trigger points but thats my 2 cents from my experimentation on myself.

I think it is a good question, rohea08.

I try not to speak in absolutes and say, “this will always respond to technique “x” while that muscle will always respond to technique “y”.”

I try and live by the mantra, “give the body what it needs”. Palpation and where you place your hands needs to be specific and that will help you dictate what to do at each structure. If you aren’t getting what you want, you may either:

a) be in the wrong spot altogether

or

b) need to change your technique/approach in order to influence the structure more appropriately

The free boarder of the upper traps are very accessible to a pincer compression and usually I will begin with that in order to get a feel for the tone of the tissue. The IT band is a rather broad, flat, piece of tissue lying over the outside of the leg (but is actucualy more the biggest thickening of the entire fascia lata which envelopes the whole leg and communicates with fascia structures both above and below it). Examination of this structure, for me, usually starts with assessing its ability to slide with the/over the underlying tissue and getting a feel for its connection to the vastus lateralis and biceps femoris.

Treatment would then depend on what I feel I need to achieve.

Patrick

Hi Michael

In the beginning of the article you wrote that “If an area of a muscle is simply tender but does not have the other characteristics of trigger points, then the area is just a “tender point”.

I have a really bad scar on my left fore arm that i got after suffering a cut 6 years ago, only recently have I noticed a dull aching pain when i put pressure on the muscle near that point, maybe it was there all along but I’m not sure.

The pain it self is not actually – directly beneath the scar but to the left of it, yet i think that the pain comes from having scar tissue near that area as when i experimented with applying pressure to that point over a few minutes.. there was no release of the pain and so I don’t think its trigger point, yet it only hurts when i press it, or stretch my forearm.

If it is a case of it being scar tissue which is causing the dis comfort, do you have any advice for me on how I could relieve myself of the pain?

It hasn’t caused a problem so far in my practise of martial art which something Ive been doing for nearly 3 years now, but I’m worried that I’ll block a kick or punch some day and will do so with the impact landing on that particular point, taking me out of the fight..

Many thanks

Jeff

Nice article. I am late to reply here but still found it very interesting.

Trigger points are localized tender spots in the muscles often detected as lumps or “knots.” Trigger points form when a muscle is injured, or overly tense. Chronic inflammation in the muscle and physical/emotional stress all contribute to “knots” and formation of scar tissue which may be helped with TPIs (trigger point injection). Trigger points can also form through time by the process of wear and tear on the muscle. Trigger points occur when normal, perpendicular muscle fibers get tangled and distorted out of their uniform pattern. Trigger points are felt as a taut band of inflamed muscle fiber and are painful when pressed.

http://pinnacleintegrative.com/medical-services/trigger-point-therapy/