Lately I’ve been neck deep in research and discussions with various people on the subject of overtraining, so I wanted to take a few minutes to post my latest thoughts on the subject. First, I’ve used HRV for the last 14+ years on well over 1000 athletes of all levels from probably more than 20 different sports, so this area is of particular interest to me. With the growing use of BioForce HRV and research on the subject in the last few years, I think this is an area where more and more questions will be answered down the road. For now though, I think there is still more confusion than answers.

If you have no idea what sympathetic and parasympathetic and autonomic regulation or HRV are, check out the free HRV Training Revolution. I’ll answer all of your HRV questions in the course and give you a strong foundation for understanding stress, why you see performance plateaus, why diets fail, etc.

Access the HRV Training Revolution

Anyway, I’ve seen various researchers and experts pose the idea recently that all athletes and individuals first reach a stage of sympathetic overreaching/overtraining and only if they continue to train do they then reach a parasympathetic state of overtraining. This hypothesis requires that everyone first responds to increased loading with an increase in sympathetic tone and a decrease in vagal input.

Personally, I think this is quite a gross oversimplification and not really the way that it works. Anytime you make blanket statements that “everyone responds like this….” you are probably going to be proven wrong sooner or later. I also don’t think that it makes sense from an allostasis point of view either and those coming to that conclusion aren’t looking at the data correctly or they aren’t seeing the big picture of ANS function at least.

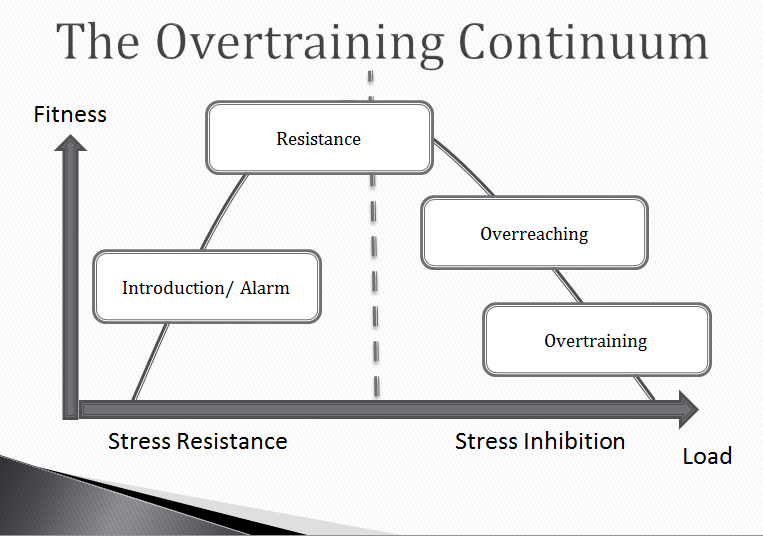

First, it’s important to define what overtraining really is. I think there is a lot of vague descriptions used and very little agreement in the literature what overtraining even is. If you can’t agree on what something is, how can you define what causes it or how the body gets to that state?

My definition of overtraining is “a state of chronic dysfunction in the body’s regulation mechanisms resulting from a prolonged imbalance between stress and recovery.” Really, this is what it comes down to. However you look at overtraining, the same underlying problem is always there, the body is persistently not responding to stress the way that it should be.

When you chronically overload the body with more stress that it can handle and adapt to, sooner or later something goes wrong in the regulation mechanics and you end up with dysfunction. Rather than this dysfunction being a very high level of sympathetic activity and a low vagal tone, however, I typically see much more often of the other side of ANS equation.

What I seem most often is that as you load an athlete, you see a gradual increase in parasympathetic tone with a corresponding decrease in sympathetic activity. From an allostatis standpoing, this makes perfect sense because it’s the body’s attempt to recover restore homeostasis as quickly as possible. The parasympathetic system is the system of recovery and the hormonal state that occurs along with it is designed to repair and rebuild.

The sympathetic system, on the other hand, should only really be active during periods of the stressor. As soon as the stressor is removed, you should see an immediate decrease of sympathetic tone and a restoration of vagal input. When you see people chronically showing high sympathetic and low parasympathetic, it’s just a sign that they aren’t able to turn off the stress response properly, or they keep reactivating it as a result of some other stressor aside from the training load.

I’ve seen this pattern quite often in people who have a high level of mental/emotional stress and are type A in general. This is also the pattern of overactive stress response that you see that has nothing to do with training whatsoever, it’s just the result of chronic stress and activation of the stress response in general. See Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers if you want to know more.

Either way, I don’t think sympathetic dominance is what should be expected from chronic overloading of stress from training and it’s not what I see most often. Instead, as the athlete accumulates fatigue, the parasympathetic system activates more and more as the body struggles to recover. This is also reflected in that when the athlete takes a day or two off from training, they actually come back showing decreased vagal tone and increased sympathetic tone.

From an allostatis standpoint, as the body faces a chronic stressor, it does its best to cope with this by turning down the stress reponse (decreased sympathetic activity) and turning up the parasympathetic drive in order to facilitate recovery. The more you load the athlete, the more this happens. More and more loading, greater and greater activation of parasympathetic system and more and more blunting of the stress reponse.

I think the body does this by first decreasing sensitivity to the hormones of the stress response (peripheral control) in the beginning and then by completely decreasing output altogether (central control) as the stress is continually applied. Patrick Ward recently sent me a paper that more or less showed this to be the case. It makes complete sense that if you continually apply a stressor that the best strategy to minimize its impact on the body is to blunt the response so that it no longer disrupts homestasis, or at least does so to a smaller degree.

I won’t get into the discussion on cytokines and the infammatory response and this aspect of the overtraining model, but it also fits in well with the allostais concept as is largely an attempt to modify behavior to get you to stop doing what you’re doing. If you feel fatigued and lethargic and feel like you shouldn’t be training in general, it’s because the body is telling you that you need to rest.

I definitely believe that the hormonal responses and control mechanisms in place have a definite function to influence behavior in a way that will encourage restoration of homeostasis, but often times people are dumb and override these signals and just keep doing what they’re doing. It’s generally when we do this that we get into trouble and push things into a state of chronic dysfunction.

In any event, I think if we look at stress and the stress response and overtraining all from an allostasis model and understand that ANS function is at the heart of the body’s control mechanisms designed to restore and maintain homeostasis, then we begin to see a more clear picture of adaptation and can develop a more accurate model of overtraining. Athletes and individuals with very well developed recovery will shift parasympathetic very quickly in the face of chronic stress. You’ll rapidly see a change in ANS towards parasymapathetic as the body adjusts regulation in favor of recovery.

People who do not have very well developed recovery and those who have a lot of emotional/mental stress and chronically overactivate the stress response in general, will have a difficult time turning the sympathetic system down and it will take them longer to get to this coping strategy. They’ll look sympathetic all the time simply because they are stressed all the time, they can’t turn the stress response off like they should. In these people, perhaps the sympathetic to parasympathetic idea fits what’s happening to some extent, but again in athletes and people with good levels of aerobic fitness and work capacity to begin with, this is rarely seen in my experience.

Anyway, those are my general thoughts on the subject at the moment. I’m doing quite a bit of HRV research looking back at athletes I’ve worked with and their ANS patterns in response to training using my BioForce HRV system. It’s all quite interesting. Stay tuned and feel free to leave comments/questions/thoughts.

I’d love to hear about your insights/experiences using BioForce HRV as well.

Joel,

Great post. I find this very interesting. I have been collecting my HRV for the past 6 months or so and the highest my HRV has been and my lowest RHR occurred after a 5 days of skiing. During these 5 days I accumulated around 15-20,000 vertical feet in 6-8 hours of skiing. Thanks to my prior training (influenced by you, Mark at PTC, and James Smith) I never felt sore or fatigued during this trip. However, according to what you said it sounds like I had a good bit of parasympathetic overreaching.

Again, great article. I look forward to the follow up.

Tank

Hey Joel,

Excellent post! I found your blog via Patrick Ward (we have corresponded on HRV a bit recently).

I have been looking at HRV for about the past 5 months now, taking 5 minute readings each morning (focusing on the RMSSD parameter which is a good proxy for parasympathetic activity). As background, I am 44 and had been fairly sedentary until this year, but am now exercising 3 or 4 times per week. My motivation for looking at HRV was to see how I might be able to improve my HRV over some reasonable period of time (my Dad had a mild heart attack last year and I would like to avoid that situation if possible).

FYI, I am using a Suunto t6d watch along with software from Firstbeat and also Kubios.

After this short period of time, I am already seeing a 40% improvement in RMSSD numbers which pleases me greatly!

While I don’t yet have any specific experience with overtraining (as you describe above), I think you are spot on with your analysis. It looks like as you overtrain, your parasympathetic may tend to act as a “governor” to restrict your power output, giving you the chance to recover.

You might want to check out this blog where an older, elite runner has cronicled his experiences with HRV, overtraining, and illness: http://canute1.wordpress.com/2009/08/31/fatigue/

All the best,

…Tim

http://soiltosustenance.wordpress.com

Tim,

Thanks for the info, I’ll be sure to check out the blog you referenced.

If you wouldn’t mind posting, what was your RMSSD to begin with and what have you managed to get it up to? I’m starting to compile a database of various HRV calculations across a broad spectrum of individuals so I’m always interested to learn where people who have specifically measured RMSSD are at.

You bet Joel.

My baseline numbers for the month of Feb. showed an RMSSD of 33.7 +/- 9.5. My current RMSSD numbers for the past week or 10 days have been about 42 or 43. I actually had a dip down in RMSSD for March, April, and part of May when I first started exercising seriously but have bounced back and then some.

You ABSOLUTELY need to get a copy of Dr. Gavin Sandercock’s paper “A Quantitative Systematic Review of Normal Values for Short-Term Heart Rate Variability in Healthy Adults.” The pubmed link to the abstract is as follows: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20663071

Unfortunately I only have a hard copy of the paper, but if you can’t get access to the full paper, let me know – I will be back at the UNC campus on Sunday and can snag a copy in PDF format.

Also, if you really want to dive deep into this, there is something called PhysioNet which you may want to look at: http://www.physionet.org/resource.shtml

Tim,

Thanks for the info, those are solid improvements in RMSSD. I’ve got a database of about 600 people’s RMSSD numbers taken from Omegawave, but more data is always better. RMSSD as a single variable of HRV is interesting, but I get the feeling that it’s not telling the whole story of stress-recovery based on my latest comparisons if it’s all you are measuring.

I’d love a .pdf of that paper, please email it to me [email protected] whenever you have access to it. Thanks for physionet link, I’ll take a look at that as well.